The Clarinet in the New York Commercial Recording Studio (Part 1)

by Mitchell Estrin

Date Posted: August 05, 2020

Photo by Jeffery Erhunse

During my years living in New York City, I was very fortunate to be a first call clarinetist for commercial recording work. This encompassed the years 1975-2000 and was during an era when studio recordings for television/radio commercials and motion picture soundtracks were commonplace. The advent of synthesizers, computer music, and the home studio have significantly decreased the number of recording sessions performed in recording studios by live musicians. I’d like to share some of the history and my recollections of being a part of a flourishing time in this amazing industry. Part 1 will focus on television/radio commercials and I will write about my experiences recording motion picture soundtracks in Part 2.

The Beginning

New York City is home to Madison Avenue, where the world’s leading advertising agencies are located. It was a natural outgrowth of the booming advertising industry to produce radio and television commercials in New York City. From the late 1950s until the early 2000s, these agencies produced thousands of commercials and most included a musical score, known in the industry as “jingles.”

The typical length for a commercial was either 30 or 60 seconds, and the advertising agencies would select from an established group of exceptionally talented composers who were experts at writing these 30 and 60 second jingles. Some of these composers were known for writing dramatic music, others for humorous music, while still others were known for writing a brilliant handful of notes that would become synonymous with a particular product. Think of such catchy tunes as the seven note Nationwide is On Your Side, nine note Like a Good Neighbor, State Farm is There, or twelve note Frosted Lucky Charms, They’re Magically Delicious.

Jingle Playing

I played in hundreds of jingles ranging from Aim Toothpaste to Xerox – airlines, beer, cars, cereals, detergents, drugs, insurance, you name it.

The sessions were typically one hour with a possible 20. This meant you were guaranteed one hour of recording and the producer or leader (this was most often the composer who also conducted) had the option to call the extra 20 minutes. Sometimes, you would be done in less than 10 minutes and be paid for the whole hour, while other times you could be there for the full 80 minutes. You never saw the music before you walked in to the studio, and often it was still being written when you arrived to warm-up. Recording musicians often joked that playing jingles was 99% taking candy from a baby and 1% sheer terror.

Most of the time, the music was not too technically difficult, but always required excellent pitch, rhythm, and style from the first reading. You had to be comfortable playing with headphones on and with a click track (imagine a metronome playing in the headphones). You never knew the instrumentation ahead of the session, so you could be part of an ensemble or the only instrument.

Time is money in the studio, so if you were not a good sight-reader with steel nerves, you didn’t last very long. The leaders knew who the players were who could read, nail it every time, and play in any musical style.

In my early years of jingle playing, you would most often record with an ensemble of musicians all recording together. As the larger studios began closing one-by-one, it became just as likely that you would record in a smaller studio with a handful of players (or even by yourself), overdubbing your part to a pre-recorded track.

Typically these sessions were layered post-production, combining the tracks for strings, woodwinds, brass, percussion, rhythm section, and singers to create the final product. Sometimes you could be asked to perform multiple parts – in my case clarinet 1 and clarinet 2 – and record each part along with the pre-recorded track. In this case, you would receive two session payments.

At each recording session, and depending on the original session booking time length, you could record a specified number of commercials, known as “spots.” Most often, you would record additional versions of the jingle with varying durations, usually 15, 30, or 60 seconds long.

Pro Tips at Recording Sessions

At the recording session, sometimes you had time to go in to the studio to set-up and play a few notes, and other times another group would finish recording and you would be called in to start almost immediately. For this reason, I would warm-up at home and leave my moistened reed ready to go on the mouthpiece. You had to be very careful walking in and around the studio, as you were in the midst of a myriad of wires, fragile and expensive recording equipment, and valuable musical instruments.

The engineers knew which microphones were best for each instrument and would have the room set up accordingly. You learned quickly the nuances of how to play in front of a microphone. Producing a pure and clean sound was important. I made sure the studio technician would aim the mic between my two hands on the clarinet and approximately 18 inches from my playing position, as I found this positioning to be optimal for jingle recording.

- If I had a solo passage, rather than playing louder to be heard, I would just lean in a little closer to the mic.

- An experienced session player would only have the headphones covering one ear, leaving the other ear uncovered to be able to listen better to themselves and to the rest of the ensemble.

- A pencil and working eraser were a must, as the composers often made changes to notes and rhythms on the fly.

- I also carried pre-printed and filled out IRS W-4 forms that I could just add the date and leave on my stand at the end of the session. These were just a few of the tricks of the trade.

Sometimes there was a video monitor in the studio and you could see the film while recording. I marveled at the amazing skill and creativity of the composers. As I became more established, I would often venture into the booth between takes to listen to the playback and watch the commercial. If I had a solo part and knew the recording engineer, I would sometimes ask for a copy of the audio recording. I still have some of these cassette recordings in my collection.

"I’d like to share some of the history and my recollections of being a part of a flourishing time in this amazing industry." - Mitchell Estrin

Payment Structure: 1970s vs Now

When I began playing jingles in the 1970s, the hourly rate for musicians specified in the collective bargaining agreement with the American Federation of Musicians was $56. This has increased incrementally over the years and is $133 per hour today. If the jingle stayed on-air beyond 13 weeks, for every subsequent 13 week cycle you received a re-use payment called a residual. This payment was typically 75% of the initial payment, so these “resids” could add up over time. Sometimes after the recording session, the advertising agency would use the same music for different commercials for the same product. A new spot could be created by changing the accompanying film, narration, length, or any other alteration to the original commercial.

Musicians received a 75% residual payment for each spot for every 13-week cycle it was played on air. A few times, I was lucky enough to play a one hour jingle and afterward the agency made a dozen (or more!) spots from the original recording of the commercial. Jingle musicians dreaded hearing sleigh bells as we knew the jingle and accompanying spots would only be seasonal and most likely not make it past the 13 week cycle. On a few occasions, I was happily surprised when the agency used the same commercial for the following year. I remember one Pillsbury Halloween spot that was used every October for over a decade.

The NYC Pros

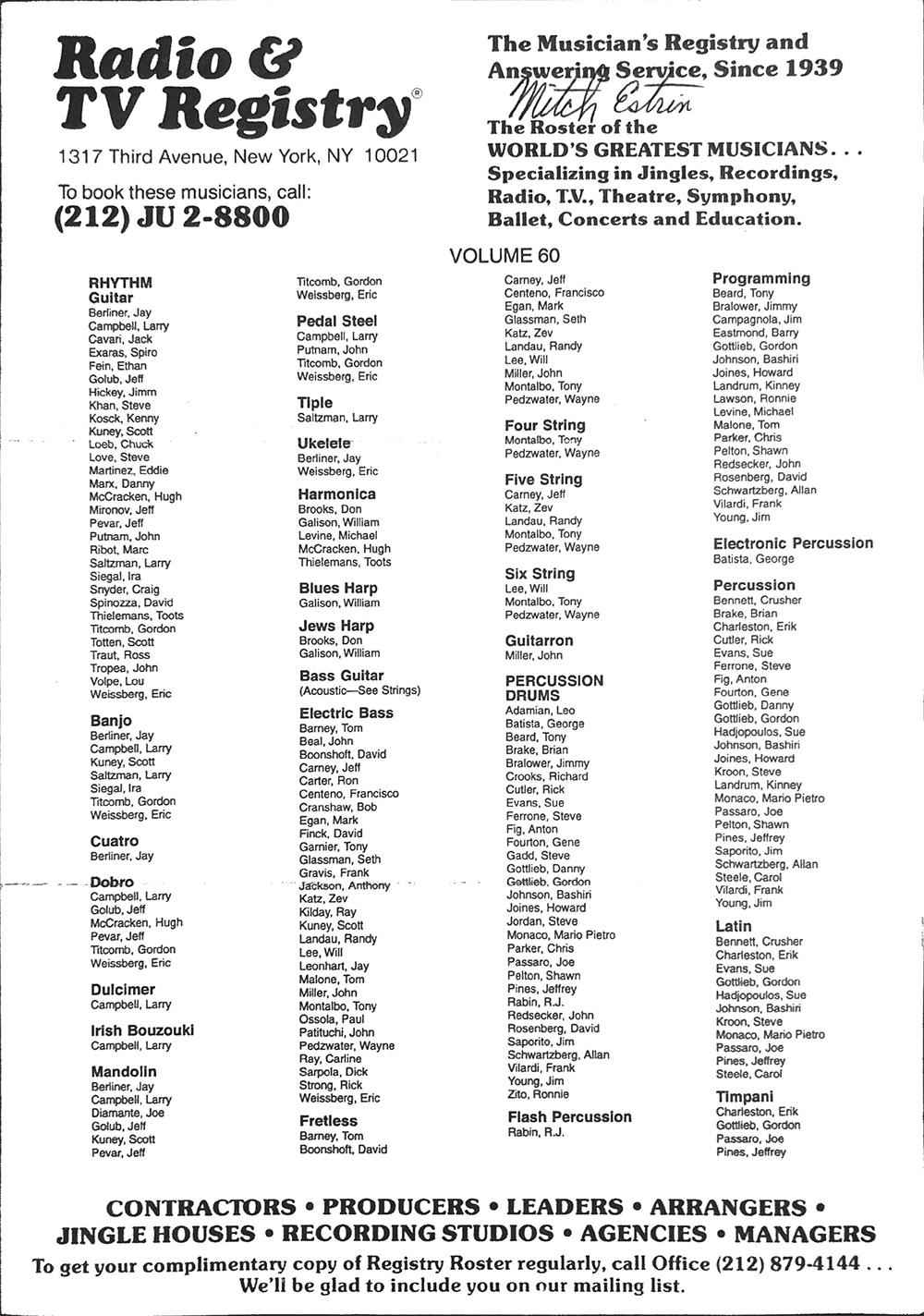

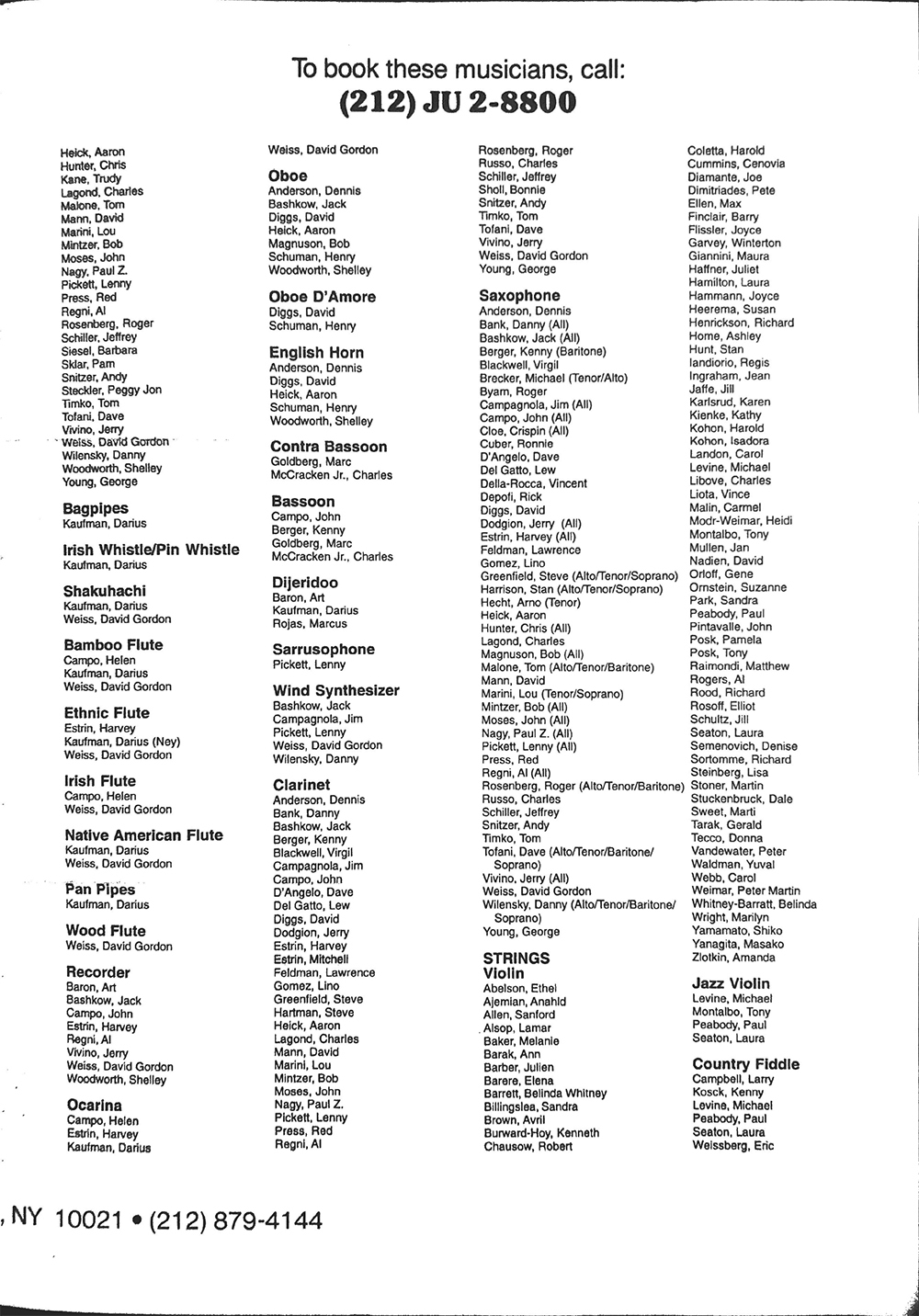

The pool of jingle musicians in New York City during that era was comprised of world class players. Some were from the Lincoln Center constituent ensembles – New York Philharmonic, Metropolitan Opera, New York City Ballet, and New York City Opera – some were from Broadway, and others were top freelancers. There was a great deal of respect, professionalism, and camaraderie among the musicians. All of the recording musicians were on the roster of the preeminent commercial music booking service, Radio & TV Registry. The “Registry” roster was referred to by musical contractors when hiring musicians for a recording session. Once the contractor received an instrumentation list from the composer, she/he would make the personnel list and send it over to Registry and their staff would put out the calls to the musicians.

Radio Registry

A typical call from Registry would sound like this: Hi Mitch, this is Maryanne from Radio Registry. I have a 10-11 with a possible 20 from Emile Charlap on Wednesday, March 2 at Automated Studio A on clarinet. Are you good for that? You would either accept (“I’m good for that”), turn-down (“sorry that’s an NG”), or occasionally “put it on hold” specifying when you would give a definite answer, but generally within 24 hours.

There were about a dozen studios in midtown Manhattan that were busy recording jingles Monday through Friday. Sadly, most, if not all of them, are closed now. Through the years you got to know everyone who worked in the studios - musicians, engineers, technical staff, administrators, and office personnel. It was a cutting-edge business where time was money and these highly-skilled professionals collaborated to produce music heard by millions around the world.

Part Two: The Clarinet in Commercial Recording

About the Author

Mitchell Estrin is Professor of Clarinet at the University of Florida and Music Director and Conductor of the University of Florida Clarinet Ensemble. He is President of the International Clarinet Association and author of the biography Stanley Drucker Clarinet Master published by Carl Fischer. Estrin performed as a clarinetist with the New York Philharmonic for over twenty years in hundreds of concerts and on 19 tours. As an international concert artist, he has performed in 37 countries on 4 continents. As a studio musician, Estrin has recorded dozens of motion picture soundtracks for Columbia Pictures, Walt Disney Pictures, Paramount Pictures, MGM, 20th Century Fox, United Artists, and Warner Brothers on feature films. They include Fargo, Beauty and the Beast, Aladdin, Interview With a Vampire, Home Alone 2, Pocahontas, Doc Hollywood, Regarding Henry, TheUntouchables, and more. His television credits include recordings for ABC, NBC, CBS, CNN, HBO, TBS, and ESPN. Learn more about Mitchell Estrin.