"It goes by very fast..." An Interview with Loren Kitt

by: Sue Heinenman

Date Posted: September 06, 2017

*This article was reused from the NSOmusicians.org Blog. Here we remember clarinetist and Vandoren Artist Loren Kitt who passed away September 2017.

A few weeks ago, Loren Kitt performed Rachmaninov’s Second Symphony for the last time in his forty-six-year NSO career. The following week, armed with a recording device and a couple of Manhattans, we sat down in the Musicians’ Lounge to talk about his career.

After admitting that he hates to listen to himself talk, Loren posed the first question.

“Do you like listening to recordings of yourself playing? I have to let it go for a while. . . . If you listen to it right away, you just remember the little things that went wrong, and you listen for those.” He then tells the story of hearing a random clarinetist on the radio and thinking, “That’s how I’d like to sound.” When the piece ended, the announcer read the name of the performer: Loren Kitt.

Loren is an apparently fearless performer. He’s certainly not one to cower before any conductor, no matter how intimidating, as anyone within range of his voice can attest. Recently, impatient with the pace of a rehearsal, he muttered, “Can we get going? I don’t have that many years left.”

Sue: Were nerves ever a thing for you?

Loren: Not really. I just had a bull-headed, straight-ahead feeling which became an obsession, especially if it went badly one night. It became like I had to do it.

I’ve been performing since I was three. My mother was big into show biz. My sister and I would entertain the troops at the Fort Lawton USO, near Seattle. I sang and danced. The buildup was the announcement: “There’s a sailor in the house.” People would boo, because it was an Army base. Then I’d come out in a little sailor’s suit.

My sister and I did nightclub acts for a while. It was a glorified variety show. I started playing drums and then switched to clarinet in fifth grade. My dad had all of Benny Goodman’s recordings, so I heard clarinet all the time, only I couldn’t play jazz.

I did athletics in junior high school—football, track, basketball. I played end, and I kicked off. I even did ballet. I liked it: really nice-looking girls! I remember the big football star saying, “Man, that takes guts!” when he heard I was doing ballet.

When I was a sophomore in high school, the Philadelphia Orchestra came to Seattle. My teacher took me to the concert, and afterward we went out with the woodwind players— Kincaid, Gigliotti, Schoenbach. I was so dazzled. They had played Tchaikovsky’s Fourth Symphony. Right then and there I knew what I wanted to do, that I wanted to be in an orchestra. My teacher said, “If you really want to do this, you can, but you’re not going to make any money.”

Sue: Did your decision make your parents nervous?

Loren: I didn’t tell them! I just wanted to do it. We were lucky; we grew up in the heyday of American orchestras.

When I broke my leg playing football in high school, that was the end of my dancing, which was fine because then I could concentrate on clarinet. I was ready; it was a good excuse. I played first clarinet with the Seattle Symphony the summer before Curtis [Institute] and also played in a lot of amateur orchestras. My dad would have lunch with the local writers, and there was always something in the paper about me. Finally I stopped telling him things because I was so embarrassed. I won an audition to play a solo with the symphony and never told him until the night of the concert. My parents were managers of a music store, so I learned all the repertoire by listening to records. I tried to copy different people’s playing—and their sounds.

Sue: Were you intimidated when you got Curtis, or did you feel like you belonged there?

Loren: What did I know, being from the West Coast? No brain, no pain! My second year I was in the finals for a principal position in Buffalo, and all of a sudden I was one of the best students. I started getting all the lead stuff at Curtis, which pissed a lot of people off, especially the seniors.

Sue: Doing something we’ve done since childhood, this becomes part of our identity. What’s it like to contemplate retirement?

Loren: It’s poignant. It goes by very fast. I’ll miss the music, of course. . . and, well, not all these people are my best friends, but they are friends, and I see them every day. When you work with a conductor, when you’re working on music, there’s a certain feeling of togetherness.

Sue: Yes, it feels quite intimate. You and I aren’t close friends, but we sit very close, breathing the same air, playing unisons.

Loren: Those are some of the greatest joys, I think, some of the notes we have together. That sort of meld— it’s not even a great solo, but it’s very pleasant. There’s a real thrill to playing some piece that you really love. Like the Prokofiev [second violin concerto] last week, such a beautiful piece. It’s the first concerto I played in the orchestra, with Menuhin and Dorati. Dorati was a fabulous conductor. I have an old recording of the Mozart clarinet concerto I did with him, and the orchestra sounds good.

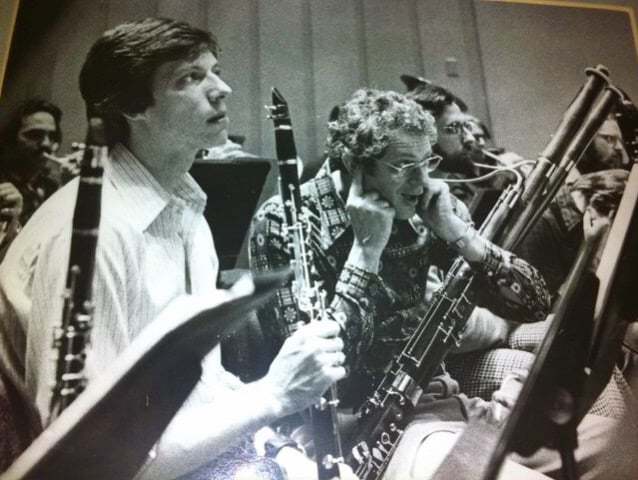

Loren with former NSP Principal Bassoonist Ken Pasmanick

Sue: Do you think there’s been a general upward trend in the quality of the orchestra, or does it go in waves?

Loren: I think waves. . . but I also think now is the best it’s ever been.

Sue: Say more about the early days.

Loren: We did Tchaikovsky’s Violin Concerto with Oistrakh. That was a thrill. Copland had a regular thing with the orchestra; I played his clarinet concerto, with him conducting, about six times. We had Milstein, Stravinsky, Leinsdorf, Abbado, Maazel, Mehta, Bernstein, Munch, Solti, Ozawa. . . . That was the thing about Slava. He would mortgage his solo playing to get conductors here who had exclusivity contracts with their orchestras: “I won’t play with your orchestra unless you conduct mine.” He was really invested in the orchestra. He wanted it to be good. What I would like to see [in the next music director] is somebody who is as dedicated to the orchestra as Slava was. Someone who would hang their star on the orchestra, so that as good as the orchestra got, they would be better too. [author’s note: this conversation took place before Gianandrea Noseda’s appointment as the NSO’s next music director but we both agreed the orchestra would be lucky to get him.]

Sue: So. . . how many times have you played Rachmaninov’s Second?

Loren: I looked it up. Fifty-four. With fifteen different conductors.

Sue: What’s next? Are you going to live full-time in Maine?

Loren: Yeah, I hate heat. The farthest south I could tolerate would be Delaware. . . . I have an alto saxophone, and I’m going to get this computer program with a rhythm section where you can play along, all the great tunes.

Sue: Why not find some people up there in Maine to play with?

Loren: It’s too embarrassing. I don’t think my ears are that good! I still can’t play jazz.