Like a Rock: Building Rhythmic Concepts with Rock-n-Roll

by Al Corley, Ph.D. Texas State University School of Music

Date Posted: August 29, 2019

Music students begin learning rhythm in the classroom at an early age. Teachers may model for several weeks before applying notation, but eventually students are introduced to rhythmic notation and the pyramid of note values. This is where problems often begin. As rhythmic notation becomes more complex, students may not connect what they see with the music they listen to every day, like rock, pop, rap, country or maybe jazz. These styles are not included in traditional band books for obvious reasons: it’s difficult to approximate a Led Zeppelin tune in a beginning band class! However, teachers should recognize that student interaction with music outside the classroom strengthens aptitude for music in the classroom. This is especially true for rhythm.

Although any style of music can be used to help students understand rhythm, rock music provides an easy way to introduce some key concepts within a musical context. “Classic rock” examples on YouTube are used in this article for ease of accessibility; however, as students learn to identify and label what they are hearing in the songs, teachers should encourage them to bring their own examples to class.

Subdivision and steady pulse

Rock and hip-hop provide great examples of steady pulse and subdivision, particularly when listening to the drum set and rhythmic “vamp”. In rock, straight 8th notes are often played as a time pattern on the high-hat, but 8th note subdivision may also be covered by the guitar or piano, as in Slash’s guitar opening of “Sweet Child of Mine” by Guns & Roses.

In this example, there’s no question that the rhythmic pulse is on the quarter note while the guitar plays even subdivision on top. Likewise, the overall pulse is steady and unwavering throughout the tune, set up by the eighth notes in the introduction:

Syncopation

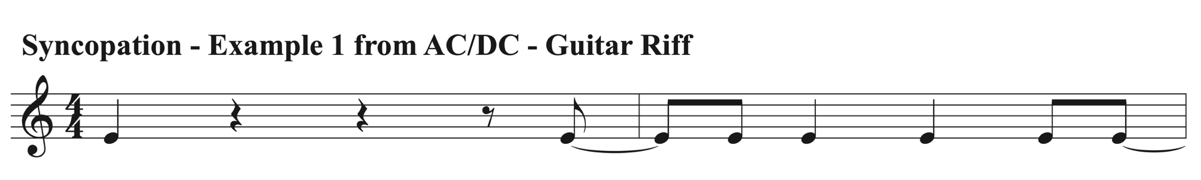

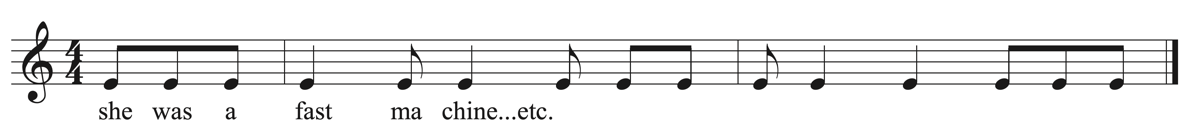

Rock tunes use syncopation in every instrumental part throughout a song, to the extent that most listeners may not even be aware of it. A rock vocal melody will almost always have a few beats of syncopation somewhere in the phrase. Vocal parts are easy to identify in a rock song, so a simple melody comprised of quarters, eighths and limited syncopation will provide an introductory example of how syncopation sounds in context. It’s rare that a syncopated figure is extended across long passages; instead, it is generally used for a few beats or to tie one measure to the next. Once students hear where melody notes shift onto the upbeat, the notation for syncopation will make more sense. Eighth notes followed by quarters will not seem so confusing. One example is AC/DC’s “You Shook Me”, which not only uses syncopation in the vocal melody but also in the primary guitar riff.

The guitar riff uses a syncopated figure across the bar line on the upbeat of 4, while the vocal melody syncopates across beat 3. The primary guitar riff starts 16 secs into the video, and the vocal melody begins at 30 secs.

Guitar Riff

Vocal Riff

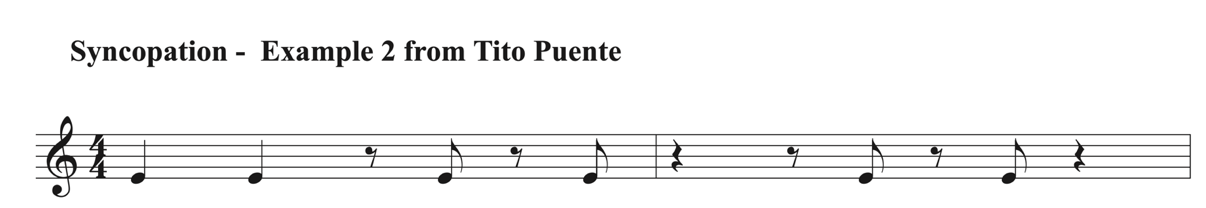

Another example of simple “upbeat” syncopation is Tito Puente’s “Oye Como Va”, covered in a rock band instrumentation by Santana. The opening organ vamp in Santana’s version syncopates a simple vamp across the bar line in an 8-beat, two-measure pattern. The quarters and eighths represent the rhythm in the simplest notation, but the performers play all of the notes the same length.

This is also an example of how rhythms may be better conceived as figures than groupings of single beats. In this case, the organ’s 2-bar rhythmic figure doesn’t make much sense when examined as individual beats or two separate measures.

In Puente’s original version for salsa band, the piano plays the rhythmic figure at a slightly faster tempo:

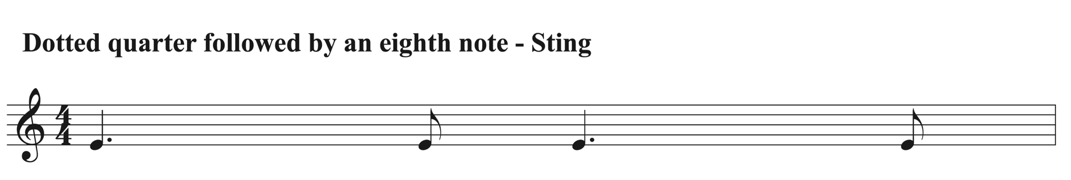

Dotted quarter followed by eighth

The rhythmic figure “dotted quarter followed by an eighth note” is often a challenge for young teachers to explain. It is similar to syncopation in that an awareness of subdivision is needed to bind the figure together. However, many teachers bog down in the math rather than focusing on the sound. Essentially, the figure (in its simplest form) is a downbeat on 1 followed by another downbeat on 3…with a pick-up to 3. The great news is that the figure represents a basic rock beat, usually played in the bass and/or bass drum. An example of the figure as a basic time pattern can be found in “Every Breath You Take” by the Police.

The song uses an ostinato eighth pattern in the guitar, but bass and bass drum play the downbeat of 1 followed by a pick-up to 3 in almost every measure. After students are able to identify the figure at this tempo, it can later be slowed down for application in lyrical settings where the subdivisions are more difficult to track.

Backbeat on 2 and 4

At its most fundamental level, music usually falls into two main styles: lyrical music (song) and rhythmic music (dance). The concept of a “backbeat” pulse is specifically relevant to the latter. Accents on 2 and 4 are so common in rock, country and jazz, it’s hard to imagine a person who cannot feel them. However, any large crowd of people clapping along with music will illuminate folks who do not recognize the difference between a natural accent on 2-4 and an accent on 1-3. Reversing the natural accent is not an accuracy problem, because a steady pulse on 1 and 3 will still match up with a song. However, the feel of music will be lost if the natural accent is mistakenly turned-around. Rock music commonly places a snare drum or clap track on 2 and 4 to make it unmistakable; therefore, rock is great source material for helping students learn the difference. Understanding the concept will not only influence how students hear music, it will also help students discover the importance of natural accents in melodic shaping. The 2-4 back beat is so intrinsic to Mark Ronson and Bruno Mars’ “Uptown Funk”, it is almost impossible to feel accents on 1 and 3.

Another example in a different style is Metallica’s “Enter Sandman”. Again, it’s difficult to clap along on 1 and 3; besides, doing so might just unleash those monsters under your bed!

Even More Concepts

Although it’s beyond the scope of this article to identify all rhythmic concepts that can be learned from rock music, the concepts presented are some of the cornerstones of “good rhythm” among performers. Additional concepts found in rock include hemiola, rhythmic counterpoint, rhythmic ostinato and “swing” eighth notes. All of these lead to an understanding of how rhythm works in music, which in turn shapes musicians’ interpretations and performances of different styles. If students start to “connect the dots” and identify rhythmic elements in the music they listen to the most, it will be easier for them to incorporate those elements into their own performances. In short, the message is this: notice how all the music out there can serve as examples in the classroom. Think outside the box, find your own examples, and rock on!

Dr. Al Corley, a native of Odessa, Texas, is an active music educator who has served the profession for over 35 years. For the past 9 years, Corley has served on the faculty at Texas State University in several capacities including student teaching supervision, music education courses, the fine arts “block, and as interim director of the Symphonic Winds. Prior to this, he served as music department chair and director of bands at Mars Hill College in North Carolina and at the University of North Texas where he supervised student teachers and taught a variety of music education classes. Prior to his work at UNT, Dr. Corley taught 19 years in the public school system of Texas, 15 of which were spent at Plano Senior High School as director of bands and co-conductor of the Plano Sr. High symphony orchestra. Currently, Corley serves as Coordinator of Graduate Studies in Music and teaches Instrumental Techniques.

Corley’s educational background includes a Bachelor of Music Education degree from Baylor University, Master of Music from Southern Methodist University, and Ph.D. in Music Education from University of North Texas.

Subscribe to the We Are Vandoren E-newsletter (WAVE) to receive 4 weekly articles for Performers, Students, and Educators